Download Scientific Basis for Exercise and more Study notes Kinesiology in PDF only on Docsity!

Exercise is Medicine

TM

Scientific Basis for Physical Activity

KIN 3534 Intro Lecture

“Eating alone will not keep a man well; he must also take exercise. For food

and exercise, while possessing opposite qualities, yet work together to

produce health. For it is the nature of exercise to use up material, but of food

and drink to make good deficiencies. And it is necessary, as it appears, to

discern the power of various exercises, both natural and artificial, to know

which of them tends to increase flesh and which to lessen it; and not only

this, but also to proportion exercise to bulk of food, to the constitution of the

patient, to the age of the individual, to the season of the year, to the changes

in the winds, to the situation of the region in which the patient resides, and to

the constitution of the year”

- Hippocrates. Regimen: Book 1, 400 BC

Most dose-response data come from longitudinal, epidemiologic based studies. Monitoring over period of time

- (^) Examine hard endpoints like all cause and CVD related mortality and incidence of disease (heart attack, stroke, or diabetes).

- (^) Examples:

- (^) Women’s Health Initiative Observational Study

- (^) Woman’s Health Study

- (^) Harvard Alumni Health Study

- (^) Aerobics Center Longitudinal Study** now called cooper study

- (^) Health Professionals’ Follow-up Study

Epidemiologic Studies

Physical Fitness and All-cause Mortality Aerobics Center Longitudinal Study (ACLS) is a prospective observational study of physical activity, physical fitness, and health outcomes among men and women.

- (^) ~10,000 men and 3,000 women followed for 8 yr for all-cause mortality in relation to initial level (quintiles) of cardiorespiratory fitness.

- (^) NOW, more than 100,000 people in the Cooper Clinic Longitudinal Study - (^) Genes Harvard Alumni Study is a prospective observational study of approximately 17,000 men who attended Harvard University between 1916 and 1950.

- FA and incidence of MI

Series 0 5 10 15 20 25 30

Women Men

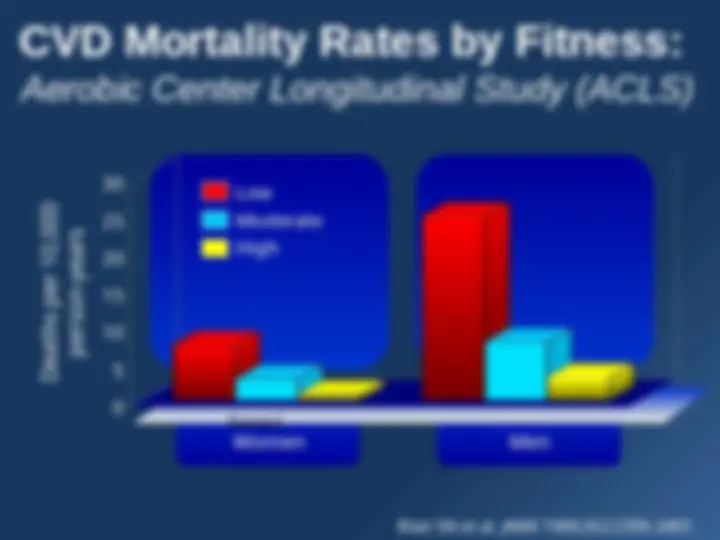

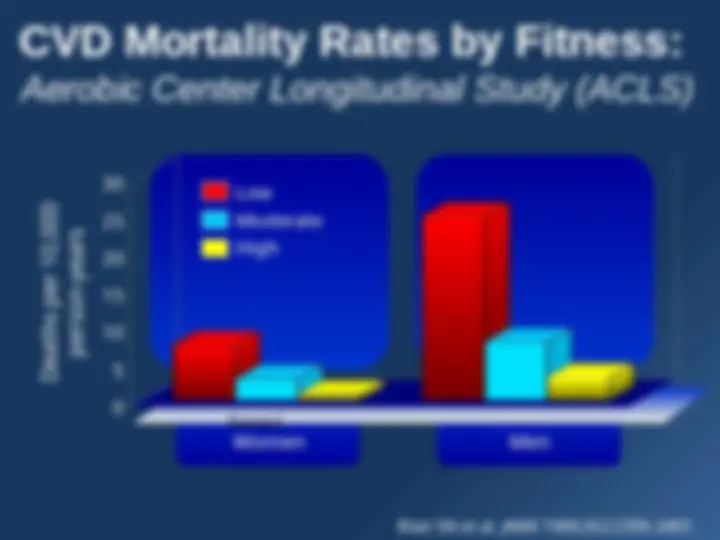

CVD Mortality Rates by Fitness:

Aerobic Center Longitudinal Study (ACLS)

Blair SN et al. JAMA 1989;262:2395-2401.

Deaths per 10,

person-years

Low

Moderate

High

Unfit–Unfit Unfit–Fit Fit–Fit

Changes in Physical Fitness and

CVD Mortality: ACLS

Blair SN et al. JAMA 1995. Series 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70

Mortality Rate

87 deaths in 9,777 men

4.9 years between exams

Fitness at Two Exams

PA an Coronary Heart Disease

• CHD is the most studied chronic disease in

relation to physical activity/fitness.

• Physical activity is cardioprotective, and

inactivity is proatherogenic.

– American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines

for the primary prevention of CVD and stroke

now emphasize regular physical activity.

– Physical inactivity is a major modifiable risk

factor for CVD.

PA and Stroke

- (^) Most studies show a trend toward an increased risk of stroke among those who are physically inactive. - (^) An inverse dose-response relationship between physical activity levels and stroke risk is generally not found. - (^) Only one study (ACLS) has examined an objective measure of cardiorespiratory fitness in relation to the risk of mortality from stroke. - (^) Men in the low-fitness category had 2.70 and 3. times the risk of stroke during the follow-up period compared with men in the moderate- and high- fitness categories, respectively.

Figures from Resource M.

PA and T2DM

- (^) Approximately 26 million (~9%) of Americans are affected by diabetes with ~95 of all cases being T2DM – CDC National Diabetes Fact Sheet - (^) The total costs associated with T2DM was estimated to be $174 billion in 2007 and is on the rise.

- (^) The progression to T2DM seems to be related to adiposity, especially in ectopic fat accumulation.

- (^) Lifestyle modification programs including diet and exercise reduce the risk of progressing to T2DM

- (^) Improving fitness is optimal for preventing early death.

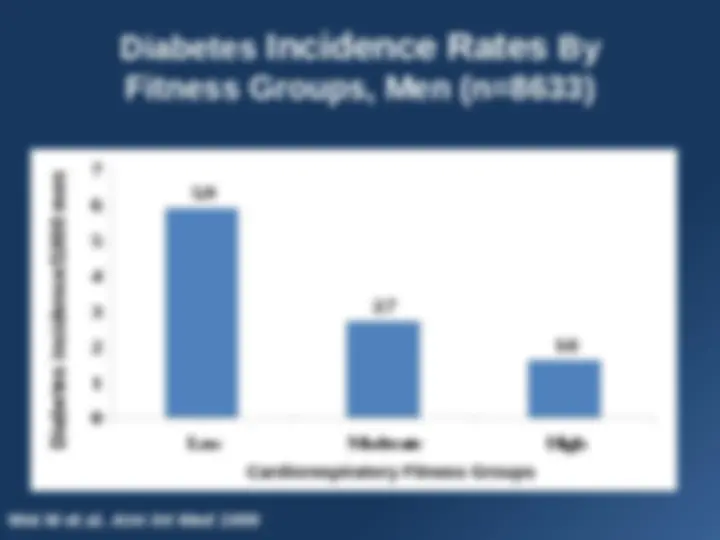

**Diabetes Incidence Rates By Fitness Groups, Men (n=8633)

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Low Moderate High Wei M et al.** Ann Int Med 1999 Cardiorespiratory Fitness Groups

Diabetes incidence/1000 men

How did they come up with the Guidelines? F.I.T.T. – Frequency, Intensity, Time, Type MET = metabolic equivalent units MET•min/wk = intensity x time/week

Exercise Dose

Optimal Dose

for Health

Health Benefits Injury Risk “Low” <3METS “Moderate” 3 to 5.9 METS “Vigorous” 6 to 8.9METS “Maximal” 9+METS From S.K. Powers and E.T. Howley. Exercise Physiology: Theory and Application to Fitness and Performance. Copyright 1990. Wm. C. Brown Publishers, Dubuque, Iowa.

Total Dose of Physical Activity

Paffenbarger et al., Am J Epidemiol , 1978 *age-adjusted first heart attack rates, 6-10 y follow-up of Harvard male alumni.

No data

concerning:

• Intensity

• Duration

• Frequency

Exercise Intensity

Intensity of PA

Lee IM et al. Circ , 2003

Age-adjusted Age + other adjusted* Relative Risk of CHD adjusted for age, smoking, alcohol use, diet, parental mortality, BMI, Hx of HTN, high Chol, diabetes. Absolute Intensity Trend P=0.01; 0.44 Relative Intensity Trend P=0.002; 0.02*

More Dose Results….

Weinstein et al. Arch Intern Med, 2008. 0-199 kcal/wk 200-599 kcal/wk 600-1499 kcal/wk ≥1500 kcal/wk No walking <1 h/wk 1-1.5 h/wk 2-3 h/wk^ ≥ 4 h/wk No walking <2.0 mph 2.0-2.9 mph ≥4 mph

Relative Risk of CHD Exercise Dose Trend P=0. Usual Pace* Trend P<0.** *adjusted for age, randomized assignment, smoking, alcohol, diet, menopause, hormone therapy, family history, and kcal expenditure Time Spent Walking Trend P<0.