Study with the several resources on Docsity

Earn points by helping other students or get them with a premium plan

Prepare for your exams

Study with the several resources on Docsity

Earn points to download

Earn points by helping other students or get them with a premium plan

Community

Ask the community for help and clear up your study doubts

Discover the best universities in your country according to Docsity users

Free resources

Download our free guides on studying techniques, anxiety management strategies, and thesis advice from Docsity tutors

The use of personal pronouns and verb tense in psychopaths and controls during storytelling. Psychopaths were found to use more first person singular pronouns, less first person plural pronouns, fewer past tense verbs, and more present tense verbs when retelling positive events than controls. These findings support the hypothesis that psychopaths show symptoms similar to the narcissistic personality disorder and use language to reflect their instrumental perspective and psychological distancing.

Typology: Lecture notes

1 / 37

This page cannot be seen from the preview

Don't miss anything!

Psychopathic Storytelling: The Effect of Valence on Self and Time in Psychopathic Language Use Honors Thesis Presented to the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, Social Science Program of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Research Honors Program by Rebecca Morrow December 2008 Research Advisor: Jeffrey Hancock

Acknowledgements I would like to thank Professor Jeffrey Hancock, my thesis advisor, for his guidance and wisdom. Without him this research would not be possible.

I would also like to thank Michael Woodworth for providing the data for this study. In addition, I would like to thank Paul Rayson for creating the Wmatrix corpus analysis program. Thank you Bruce Lewenstein for providing me with guidance throughout my academic career at Cornell University.

I would like to thank my family who have supported me throughout my lifetime and inspired a passion for new ideas and research.

Introduction

Theophrastus, a student of Aristotle, was deft at characterizing personality types. His ―Unscrupulous Man‖ portrays characteristics of the modern conception of psychopaths:

The Unscrupulous Man will go and borrow more money from a creditor he has never paid…When marketing he reminds the butcher of some service he has rendered him and, standing near the scales, throws in some meat, if he can, and a soup-bone. If he succeeds, so much the better; if not, he will snatch a piece of tripe and go off laughing. (Qtd. in Millon, Simonsen, & Birket- Smith, 1998, p. 3)

Theophrastus shows psychopaths as eager to cheat and lacking in remorse. Today, psychologists agree that psychopaths share a number of characteristics including egocentricity, impulsiveness, shallow emotions, little empathy, guiltlessness, pathological lying, and a willingness to violate social norms (Hare, 1998). In addition to these distinctive personality characteristics, psychopaths have a high propensity for crime: in a federal offender sample, psychopaths committed an average of 7.32 violent crimes compared with an average of 4.52 violent crimes for nonpsychopathic offenders (Porter & Porter, 2007). Within one year of committing violent crimes, psychopaths are more likely than nonpsychopaths to be repeat offenders for additional serious violent crimes (Porter & Porter). Psychopaths, however, present themselves as normal people, wearing a ―mask of sanity‖ according to Cleckley (1941). The purpose of this study is to examine the language of psychopathic offenders for evidence of egocentricity, narcissism, and psychological distancing that may leak out from behind their mask.

Main Attributes of the Psychopath

Psychopaths are most commonly identified by the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (PCl-R), a 20-item instrument (Hare & Neumann, 2006). Scores on the PCL-R are determined by semistructured interviews and information from files. Each of the 20 items is scored on a 3-point scale from 0-2, so scores can range from 0-40. The criteria to diagnose psychopaths in North America are scores above 30 on the PCL-R. Some of the items are ―glibness/superficial charm … grandiose sense of self worth … pathological lying … lack of remorse or guilt … shallow affect … juvenile delinquency‖ (Hare & Neumann, p. 63), which are cornerstone descriptions of psychopathic personality. PCL-R scores can be analyzed in terms of underlying factors. In 1991, the PCL-R was divided into two factors: Factor 1, Interpersonal/Affective; and Factor 2, Social Deviance (Hare & Neumann). In 2003, Hare divided the PCL-R analyses into four factors: interpersonal, affective, lifestyle, and antisocial.

Psychopaths are known for their egocentricity and inability to love (Lykken, 1995). They have trouble forming deep attachments to other people, and according to Levenson, this ―trivialization of the other,‖ needs to be researched further in psychopathy studies (qtd. in Blackburn, 2006, p. 50). Evidence also shows that psychopaths are motivated by thrill seeking and sadistic interests (Porter & Woodworth, 2006). Psychopaths show more violence when they commit sexual crimes (Gretton, McBride, Lewis, O‘Shaugnesssy, & Hare, 1994 qtd. in Porter & Woodworth, 2006), and take advantage of others more often in their crimes (Forth & Kroner, 1995 qtd. in Porter & Woodworth). In addition, when psychopaths describe their crimes, they tend to reframe their experiences by shifting blame away from themselves,

He found that when faced with an imminent threat of electric shock, psychopathic offenders show a significantly reduced conditioned response compared to non-psychopaths (Blair et. al, 2005). However, few studies examined the differences between psychopathic offenders‘ and non-psychopathic offenders‘ responses to positive stimuli. One study examined how differently valenced images affected the startle response in non-psychopaths, mixed offenders, and psychopathic offenders. The normal, mixed, and psychopathic groups did not differ in startle blink magnitude during neutral and positively valenced images, but psychopathic offenders displayed a significantly lower startle blink magnitude during negative images (Patrick, 2007).

Language and Psychopaths Note that these studies analyzed psychopath‘s language processing, but few studies have examined the way psychopaths use language. Psychopaths have been found to produce more disfluencies, such as ―uh‖ or ―um,‖ compared to controls when discussing their murders, which suggests that retelling such an emotional story was uncomfortable for them (Woodworth, Hancock, and Porter, 2008). In one recent study examining language production, Kornet (2008) found when offenders speak about their murders, psychopaths produce fewer emotional references than non-psychopaths. Overall, psychopaths use emotional terms less frequently, and the emotional terms they use are more negatively valenced than controls (Kornet, 2008). These findings are consistent with psychopaths‘ shallow affect. What other personality traits unique to psychopaths might be reflected in their language use?

One possibility is that psychopaths often display characteristics consistent with the narcissistic personality, such as an aggressive-sadistic personality style, self-love, arrogance,

and other-exploitation. Indeed, psychopathy is often present at the same time as, or co- morbid with, narcissistic personality disorder (Widiger, 2006). Stone (1993) notes that: ―all psychopathic persons are at the same time narcissistic persons‖ (qtd. in Widiger, 2006, p. 162). However, narcissistic people feel guilt and remorse due to their negative actions, unlike psychopaths (Widiger, 2006). The fact that psychopaths tend to exhibit narcissism is potentially important as there appears to be a link between narcissistic personality disorder and personal pronoun use. The use of ―I‖ in language can be interpreted as a measure of egocentrism because its primary function is to distinguish between the self and the other (Raskin & Shaw, 1988). In one experiment, Raskin and Shaw (1988) asked subjects to talk about a topic of their choice for 5 minutes. After the monologue, subjects took the Narcissistic Personality Inventory, the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire, and the Rotter Internal-External Locus of Control Scale. They found that subjects with higher narcissism scores used ―I‖ more and ―we‖ less than subjects with lower narcissism scores (Raskin & Shaw, 1988).

Another important aspect of the psychopath that may be reflected in their language is the process of psychological distancing. According to Renninger and Cocking (1993, p. 24), psychological distance ―refers to the way in which the individual equilibrates and represents information for him- or herself.‖ The concept of psychological distance was influenced by Piaget‘s theory of the stages of cognitive development in children, as it referred to children being able to separate objects from their physical appearances (Siegel and McGillicuddy-De Lisi, 2003). Siegel and Cocking implemented a program, Educating the Young Thinker , which aimed to study psychological distancing in children. They would put children in situations where they had ―to separate himself or herself mentally from the here and now and

Research Questions/Empirical Hypothesis Given that psychopaths show a high co-morbidity with narcissism, and that narcissism is linked with higher rates of first person singular pronoun use, psychopaths should produce higher rates of personal pronouns and lower rates of other-oriented pronouns than controls. H1: Psychopaths will use first person singular pronouns (―I‖ ―me‖) more frequently than controls H2: Psychopaths will use first person plural pronouns (―we‖ ―us‖) less frequently than controls H3: Psychopaths will use third person singular personal pronouns such as (―he‖ ―she‖) less frequently than controls As noted above, psychological distancing is reflected in verb tense. If this is the case, both psychopaths and controls should produce more past tense verbs when describing negative stories in their past than during positive stories. Conversely, they should produce more present tense verbs when describing positive stories than during negative ones.

H4a: In general, more past tense verbs should be used when describing negative events relative to positive events H4b: In general, more present tense verbs should be used when describing positive events relative to negative events

Given that psychopaths tend to feel less guilt and show less remorse than controls, psychological distancing should be more salient in psychopathic language than in non-

psychopathic language. Thus, psychopaths should use less past tense verbs when describing negative events and more present tense verbs during positive events. H5a: When describing negative events, psychopathic offenders will use more past tense verbs than controls. H5b: When describing positive events, psychopathic offenders will use less past tense verbs than controls. H6a: When describing negative events, psychopathic offenders will use less present tense verbs than controls. H6b: When describing positive events, psychopathic offenders will use more present tense verbs than controls.

life event, meeting his father for the first time, and provides the interviewer with a lot of information: Oh, okay. My father left...or was removed from our family when I was 4. I went through a period of blaming myself for that…that I thought I had done something wrong, and he was punishing me. So, I went through a lot of my whole adult life, afterwards punishing myself. But in 1975, my grandmother…give me his address where he was. So, I went to live with him, unbeknownst to him. While - my grandmother and myself, and everyone else, we lived in Halifax, and my father was living up in Virginiatown, Ontario - a little remote community of about 3500 up in Northern Ontario. You know where Kirkland Lake is? Linguistic Analysis Transcripts were analyzed using quantitative text analysis. Transcripts were analyzed for parts of speech categories using Wmatrix corpus analysis and comparison tool (Rayson, 2003, 2008b). Wmatrix uses the Constituent Likelihood Automatic Word-tagging System, or CLAWS, to code for parts-of-speech (i.e. pronoun, verb, noun, etc.) based on surrounding linguistic context (i.e. ―laugh‖ can be a verb or a noun depending on its surrounding context) (Rayson, 2008a). CLAWS consistently achieves an accuracy rate of 96-97% in classifying parts-of-speech (Rayson, 2008a). Transcripts were combined together into six groups: psychopaths speaking about positive events (N=13), psychopaths speaking about negative events (N=11), controls speaking about positive events (N=34), controls speaking about negative events (N=35), a combined group of psychopaths speaking about both positive and negative events, and a combined group of controls speaking about both positive and negative

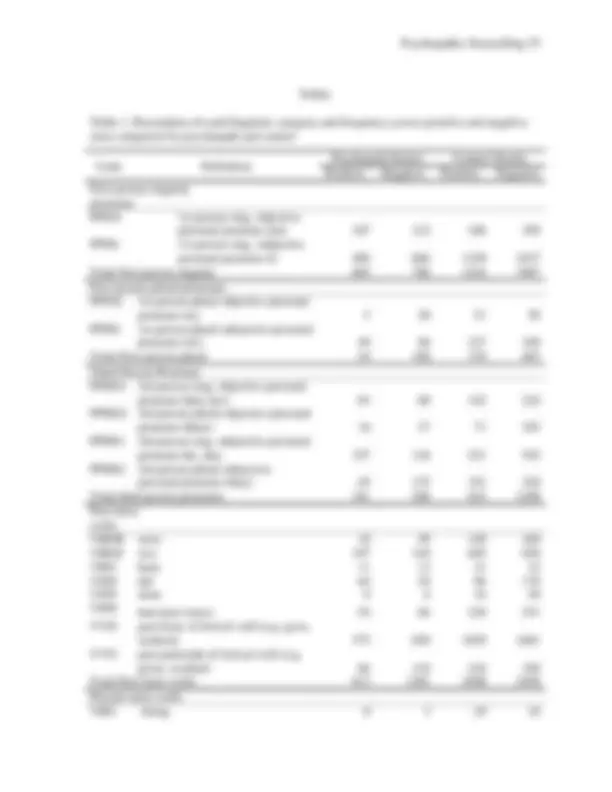

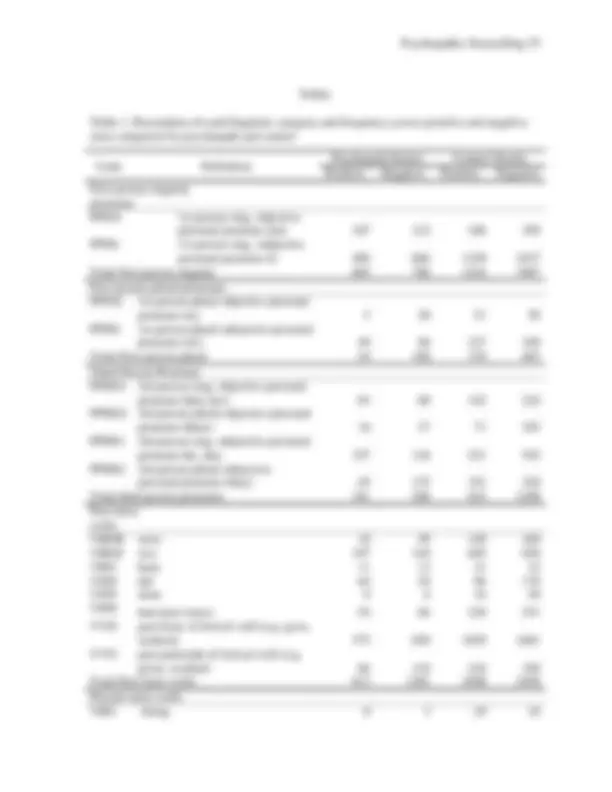

events. Significance levels were determined by one degree of freedom log-likelihood ratios ( LLR) , which were calculated from contingency tables of pronoun or verb frequencies in each group. The results were significant if LLR > 7. The transcripts were analyzed in terms of pronoun and verb use, specifically the use of self-related pronouns, self plural pronouns, third person pronouns, past tense verbs, and present tense verbs. Self-related pronouns were defined as the first person singular objective personal pronoun, ―me,‖ and the first person singular subjective personal pronoun, ―I.‖ Self plural pronouns were defined as first person plural objective personal pronoun, ―us,‖ and first person plural subjective personal pronoun, ―we.‖ Third person pronouns were defined as the objective personal pronoun, ―him,‖ or ―her,‖ plural objective personal pronoun, ―them,‖ singular subjective personal pronoun, ―he,‖ or ―she,‖ and plural subjective personal pronoun, ―they.‖ The present analysis does not include the use of second person pronouns ―you‖ or ―yours.‖ Past tense verbs were defined as ―were‖ ―was‖ ―been‖ ―did‖ ―done‖ ―had,‖ past tenses of lexical verbs such as, ―worked,‖ and past participles of lexical verbs ―given.‖ Present tense verbs were defined as ―being, am, are, is, do, doing, does, having, has,‖ base forms of lexical verbs such as ―give,‖ and –s forms of lexical verbs such as ―works,‖ (See tables 11-15).

psychopaths used more first person plural when describing negative events ( freq = 108, relative freq = 1.07%) compared to positive events ( freq = 54, relative freq = 0.61%), LLR = 8.95, p < 0.01. These results suggest that psychopaths use less first person plural pronouns when describing events in their lives, but the effects are most salient when describing positive events (See Figure 2). The results supported H2, which predicted that psychopaths would use first person plural pronouns less frequently than controls. Third person analysis. Psychopaths used less third person language when speaking about negative events ( freq = 368, relative freq = 3.36%) than controls ( freq = 1,208, relative freq = 4.4%), LLR = 12.17, p < .001. There were no other significant effects (See Figure 3). The results partially supported H3, which predicted that psychopaths would use third person singular personal pronouns less frequently than controls. Taken together, these pronoun patterns suggest that the narcissistic nature of psychopaths is reflected in their pronoun use, and that their increased self-focus increases when discussing positive events. Psychological Distancing and Verb Tense Analysis Past tense analysis. Consistent with psychological distancing, offenders used more past tense during negative events ( freq = 4,751, relative freq = 11.80%) than during positive events ( freq = 3,303, relative freq = 9.96%), LLR = 56.36, p < 0.0001. The results support H4a, which predicted that during negative events, psychological distancing would be evidenced in a general increase in past tense verbs compared to positive events. Overall, psychopaths ( freq = 2,114, relative freq = 10.64%) did not differ from controls ( freq = 5,940, relative freq = 11.09%) in their use of past tense verbs LLR = 2.69, ns. The question of interest, however, was how the valence of the story affected past tense verb production for psychopaths compared to controls. H5a predicted that during negative events, psychopaths

would use more past tense verbs than controls. This hypothesis was not supported. Psychopaths ( freq = 1,301, relative freq = 12.88%) and controls ( freq = 3,450, relative freq = 12.55%) produced the same rate of past tense verbs during their telling of the negative stories, LLR = 0.08, ns. A difference did emerge, however, during positive events. As predicted, psychopaths used less past tense ( freq = 813, relative freq = 9.12%) than controls ( freq = 2,490, relative freq = 11%) during positive events, LLR = 8.84, p < 0.01. The results supported H5b, which predicted that during positive events, psychopathic offenders would use less past tense verbs than controls. The results suggest that offenders use less past tense overall when telling positive stories, but the effect is more salient when psychopaths tell positive stories (See Figure 4). Present tense analysis. Consistent with psychological distancing, offenders used more present tense during positive events ( freq = 1,930, relative freq = 5.82%) than during negative events ( freq = 1,687, relative freq = 4.19%), LLR = 97.59, p < 0.0001. The results supported H4b, which predicted that during positive events, offenders in general would use more present tense verbs than during negative events. Overall, psychopaths ( freq = 1,012, relative freq = 5.10%) and controls ( freq = 2,605, relative freq = 4.87%) did not differ in their use of present tense verbs, LLR = 1.54, ns. The key question was whether the valence of the story affected present tense usage differently in psychopaths and controls. H6a predicted that during negative events, psychopaths would use less present tense verbs than controls. This hypothesis was not supported. During negative events, psychopaths ( freq = 429, relative freq = 3.92%) and controls ( freq = 1,258, relative freq = 4.58%) produced the same rate of present tense verb usage during the retelling of their negative stories, LLR = 2.7, ns. Similar to the pattern found during past tense verb usage, a difference emerged during positive

Discussion This study aimed to uncover language differences in storytelling between psychopathic and non-psychopathic offenders. The research focused on psychopathic language use and whether it highlighted their self-centered and remorseless nature. The research focused on two traits specific to the psychopath: characteristics consistent with the narcissistic personality disorder, and the manner in which they psychologically distance themselves differently than controls. Psychopaths were expected to use more language referring to themselves, less language referring to other people, and show more salient psychological distancing effects than controls through their use of past and present verb tenses. Narcissism Consistent with the predictions, psychopaths used more first person singular pronouns

experience, so the effects of narcissism are evident when the psychopathic offender fails to mention the two other important people involved in the experience. Also consistent with the predictions stemming from the narcissistic nature of psychopaths, psychopaths used significantly less first person plural pronouns than controls. Furthermore, psychopaths increased their use of first person plural pronouns during negative events, consistent with Porter and Porter‘s (2007) observation because the results suggest that psychopaths are more instrumental in their descriptions of the crime. They are less likely to blame themselves, so they speak about their accomplice in addition to themselves. For example, one psychopathic offender recalls an experience of a bank hold-up: Well, for the bank and that I was part of a few guys there, and uh, for us, it was, I wasn't ready and uh, I was really intoxicated, coke and everything now, and uh, and uh when we do bank it was like uh, to get some more money to spend and have fun and it was uh, like a challenge to do that because sometimes we do, three guys we go and uh, we do them all at the day, you know, sometimes we do three a day, we do bank, and we do them all bank, and on that time, that's year seventy, that was long time ago and uh, on this time uh, the bank was easy to do, you know, they give you the money and that was it, and you leave, and we never think about the consequences of that. Note that the psychopathic offender shifts blame away from himself and onto his friends by using the pronoun ―we.‖ Even more importantly, the psychopath mentions that he never thought about the consequences of his actions using ―we‖ as the sentence subject. The psychopathic lack of guilt and remorse is resilient in this subject‘s speech. When psychopaths