Study with the several resources on Docsity

Earn points by helping other students or get them with a premium plan

Prepare for your exams

Study with the several resources on Docsity

Earn points to download

Earn points by helping other students or get them with a premium plan

Community

Ask the community for help and clear up your study doubts

Discover the best universities in your country according to Docsity users

Free resources

Download our free guides on studying techniques, anxiety management strategies, and thesis advice from Docsity tutors

A scientific article published in The Open Bioinformatics Journal in 2008. The authors, Subhash Mohan Agarwal and Atul Grover, discuss the nucleotide composition, codon usage, and amino acid content in hyperthermophilic species. They found that arginine, proline, valine, and tyrosine were the most abundant amino acids in hyperthermophilic proteomes, and similar biases were seen when dipeptidic composition of proteins was compared. The study also suggested that elevated growth temperature imposes selective constraints at all three molecular levels: nucleotide composition, codon usage, and amino acid content.

What you will learn

Typology: Study Guides, Projects, Research

1 / 9

This page cannot be seen from the preview

Don't miss anything!

The Open Bioinformatics Journal, 2008, 2, 11-19 11

1875-0362/08 2008 Bentham Science Publishers Ltd.

1

*Address correspondence to this author at the Bioinformatics Center, School of Information Technology, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi 110067, India; E-mail: smagarwal@yahoo.co.in

12 The Open Bioinformatics Journal, 2008, Volume 2 Agarwal and Grover

Species Name Abbreviation GC Content OGT (°C)

Mesophile

Campylobacter jejuni Cjej 31 43

Borrelia burgdorferi Bbur 28 37

Lactococcus lactis Llac 35.3 30

Rickettsia prowazekii Rpro 29 35

Hyperthermophile

Methanococcus jannaschii Mjan 31.3 85

Sulfolobus solfataricus Ssol 35.8 80

Sulfolobus tokodaii Stok 32.8 80

Nanoarchaeum equitans Nequ 31.6 90

14 The Open Bioinformatics Journal, 2008, Volume 2 Agarwal and Grover

Nucleotide Cjej Bbur Rpro Llac Avg-Meso Mjan Ssol Stok Avg-Thermo Nequ Avg-thermo+ Nequ

AT 10.0 11.1 11.8 9.1 10.5 10.9 9.7 10.3 10.3 ns 11.3 10.6 ns

AC 3.4 3.3 4.2 4.7 3.9 3.5 4.6 4.3 4.1 ns 4.0 4.1 ns

AA 16.1 16.7 14.2 13.5 15.1 15.3 11.6 12.8 13.2 ns 16.7 14.1 ns

TA 9.1 9.5 11.7 6.5 9.2 9.4 10.2 10.8 10.1 ns 11.5 10.5 ns

TG 6.5 6.0 5.8 7.5 6.4 6.8 5.6 5.7 6.0 ns 4.9 5.7 ns

TC 3.5 3.8 3.8 5.2 4.1 2.9 4.3 4.1 3.7 ns 2.6 3.5 ns

CA 4.7 4.7 5.0 6.0 5.1 4.7 4.7 4.6 4.7 ns 4.6 4.6 ns

CT 4.9 4.6 4.8 5.3 4.9 3.8 5.2 5.3 4.8 ns 3.9 4.6 ns

CG 1.4 1.0 1.8 2.5 1.7 0.7 2.2 1.5 1.4 ns 1.4 1.4 ns

CC 1.7 1.8 1.7 2.6 2.0 2.0 2.8 2.4 2.4 ns 3.0 2.6 ns

GC 4.2 3.1 3.5 3.9 3.7 2.9 3.1 2.9 3.0 ns 3.3 3.0 ns

GT 4.1 3.6 4.7 4.7 4.3 4.3 5.2 4.9 4.8 ns 3.8 4.5 ns

The values shown are the percentage of dinucleotides in the complete coding sequences of each genome. Mean values for the mesophilic (Avg-meso) and hyperthermophilic (Avg- thermo; Avg-thermo+nequ) are shown. Also significance based on a t-test are shown. ns (p>0.05); * (p<0.05); *** (p<0.001).

Nucleotide Composition and Amino Acid Usage in AT-Rich The Open Bioinformatics Journal, 2008, Volume 2 15

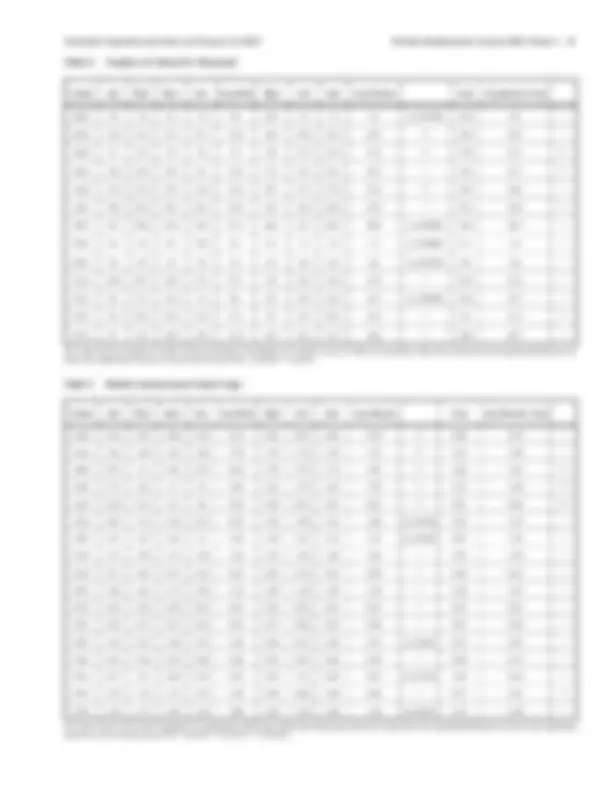

Codon Cjej Bbur Rpro Llac Avg-Meso Mjan Ssol Stok Avg-Thermo Nequ Avg-thermo+ Nequ

GGG 5.8 7.8 5.6 7.8 6.8 10.4 9.7 7.3 9.1 ns (0.0790) 10.4 9.4 *

GAG 12.8 17.6 13.3 11.7 13.8 34.8 29.4 23.0 29.1 ** 18.9 26.5 *

AGG 2.7 6.4 3.4 1.4 3.5 9.8 17.5 11.9 13.1 ** 11.8 12.7 **

AUU 43.7 59.6 51.9 53.6 52.2 48.6 33.7 40.3 40.8 ns (0.0850) 30.4 38.2 *

CGU 6.4 1.8 9.5 15.0 8.2 0.3 1.7 1.4 1.1 ns (0.0860) 0.7 1.0 *

CGC 3.8 0.9 1.9 3.9 2.6 0.1 0.6 0.4 0.4 ns (0.0520) 0.6 0.4 *

CAA 28.4 18.7 24.6 31.1 25.7 9.0 15.5 15.6 13.4 * 20.5 15.2 *

CUA 6.8 8.7 11.6 7.4 8.6 8.5 19.2 16.4 14.7 ns (0.0940) 18.4 15.7 *

CUU 32.1 30.5 20.4 25.5 27.1 9.1 15.2 18.6 14.3 * 6.4 12.3 **

The values shown are number of codons within each genome. The numbers are scaled to a total of 1000 for each genome. Only those codons that show significant differences are listed. Also significance based on a t-test are shown. ns (p>0.05); * (p<0.05); ** (p<0.01).

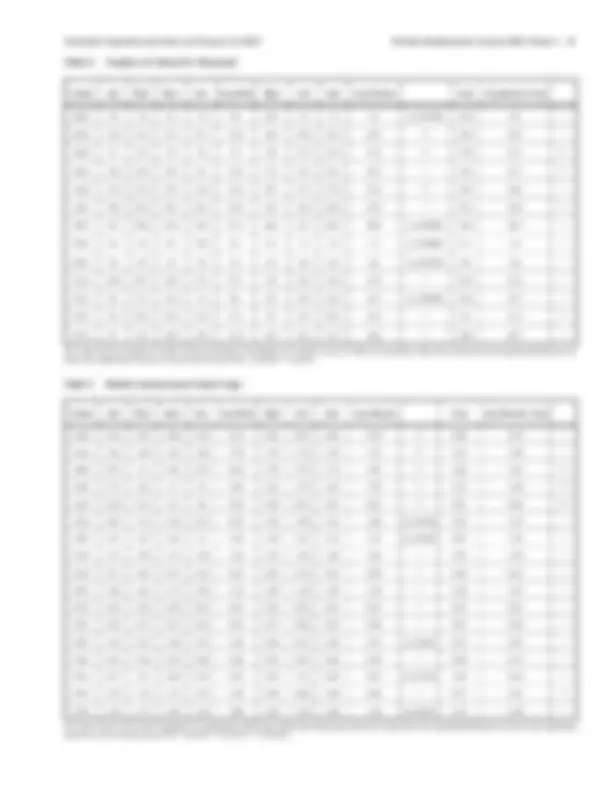

Codon Cjej Bbur Rpro Llac Avg-Meso Mjan Ssol Stok Avg-Thermo Nequ Avg-Thermo+ Nequ

AUA 0.91 1.12 1.26 0.33 0.91 1.30 1.58 1.51 1.46 ns (0.078) 1.91 1.11 *

AUU 1.52 1.67 1.43 2.1 1.68 1.39 1.07 1.22 1.23 ns (0.065) 0.87 1.51 *

UAU 1.73 1.59 1.73 1.58 1.66 1.55 1.30 1.48 1.44 * 1.56 1.59 *

UAC 0.27 0.41 0.27 0.42 0.34 0.45 0.70 0.52 0.56 * 0.44 0.41 *

UUU 1.86 1.81 1.71 1.58 1.74 1.59 1.19 1.39 1.39 * 1.38 1.57 *

UUC 0.14 0.19 0.29 0.42 0.26 0.41 0.81 0.61 0.61 * 0.62 0.43 *

UCC 0.18 0.27 0.23 0.26 0.24 0.37 0.68 0.43 0.49 * 0.67 0.38 *

CGU 1.29 0.33 1.69 2.52 1.46 0.04 0.21 0.20 0.15 ns (0.06) 0.11 1.03 *

CGC 0.76 0.16 0.34 0.66 0.48 0.01 0.07 0.06 0.05 * 0.09 0.31 *

CUA 0.37 0.5 0.69 0.45 0.50 0.54 1.11 0.96 0.87 ns (0.075) 1.06 0.64 *

CUU 1.78 1.76 1.21 1.55 1.58 0.58 0.88 1.09 0.85 * 0.37 1.02 **

CCU 2.34 1.77 2.01 1.45 1.89 1.02 1.30 1.46 1.26 ns (0.051) 1.25 1.40 *

The values shown are the relative frequencies of synonymous codon usage within each codon group. Only those codons that show significant differences are listed. Also significance based on a t-test are shown. ns (p>0.05); * (p<0.05); ** (p<0.01); *** (p<0.001).

Nucleotide Composition and Amino Acid Usage in AT-Rich The Open Bioinformatics Journal, 2008, Volume 2 17

Charged Polar Charged-Polar

Percentage

Mesophilic

Hyperthermophilic

Hyperthermophilic including N. equitans

18 The Open Bioinformatics Journal, 2008, Volume 2 Agarwal and Grover

[1] R. M. Atlas, and R. Bartha, “Microbial ecology-fundamentals and applications”, Pearson Education (Singapore) Pte. Ltd, pp. 305- 311, 2005. [2] D. W. Grogan, “Hyperthermophiles and the problem of DNA in- stability”, Mol. Microbiol. , vol. 28, pp. 1043-1049, 1998. [3] R. J. Klein, Z. Misulovin, and S. R. Eddy, “Noncoding RNA genes identified in AT-rich hyperthermophiles”, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA , vol. 99, pp. 7542-7547, 2002. [4] N. Galtier, and J. R. Lobry, “Relationships between genomic G+C content, RNA secondary structures, and optimal growth tempera- tures in prokaryotes”, J. Mol. Evol. , vol. 44, pp. 632-636, 1997.

[5] S. Das, S. Paul, S. K. Bag, and C. Dutta, “Analysis of Nanoar- cheum equitans genome and proteome composition: indications for hyperthermophilic and parasitic adaptations”, BMC Genomics , vol. 7, pp. 186, 2006. [6] D. P. Kreil, and C. A. Ouzounis, “Identification of thermophilic species by the amino acid compositions deduced from their ge- nomes”, Nucleic Acids Res , vol. 29, pp. 1608-1615, 2001. [7] R. Schwartz, C. S. Ting, and J. King, “Whole proteome pI values correlate with subcellular localizations of proteins for organisms within the three domains of life”, Genome Res , vol. 11, pp. 703- 709, 2001. [8] J. R. Lobry, and D. Chessel, “Internal correspondence analysis of codon and amino-acid usage in thermophilic bacteria”, J. Appl. Genet. , vol. 44, pp. 235-261, 2003. [9] R. Friedman, J. W. Drake, and A. L. Hughes, “Genome-wide pat- terns of nucleotide substitution reveal stringent functional con- straints on the protein sequences of thermophiles”, Genetics , vol. 167, pp. 1507-1512, 2004. [10] K. U. Foerstner, C. von Mering, S. D. Hooper, and P. Bork, “Envi- ronments shape the nucleotide composition of genomes”, EMBO Rep. , vol. 6, pp. 1208-1213, 2005. [11] J. Garnier, J. F. Gibrat, and B. Robson, “GOR method for predict- ing protein secondary structure from amino acid sequence”, Meth- ods Enzymol. , vol. 266, pp. 540-553, 1996. [12] T. Kawashima, N. Amano, H. Koike, et al , “Archaeal adaptation to higher temperatures revealed by genomic sequence of Thermo-