Study with the several resources on Docsity

Earn points by helping other students or get them with a premium plan

Prepare for your exams

Study with the several resources on Docsity

Earn points to download

Earn points by helping other students or get them with a premium plan

Community

Ask the community for help and clear up your study doubts

Discover the best universities in your country according to Docsity users

Free resources

Download our free guides on studying techniques, anxiety management strategies, and thesis advice from Docsity tutors

This master's thesis explores the professional identity of STEM students by investigating their self-concept and the match with the professional identity of an engineer. The study also examines the relationship between identity status and career choices, using a card-sorting activity and quantitative results. The research aims to provide insights into the development of professional identities and the factors influencing career choices in the STEM field.

Typology: Thesis

Uploaded on 03/31/2022

1 / 45

This page cannot be seen from the preview

Don't miss anything!

Carlijn Veldhorst 1st Supervisor: R. van Veelen 2nd Supervisor: M. D. Endedijk Master Thesis Educational Science and Technology 30-3-

Title of the final project

Researcher Carlijn Veldhorst, c.veldhorst@student.utwente.nl

Supervisors R. van Veelen, r.vanveelen@utwente.nl

M. D. Endedijk, m.d.endedijk@utwente.nl

Keywords STEM-students, professional identity, identity status, self-to-prototype matching, career choice

Acknowledgement ....................................................................................................................................

Although more and more students choose for a technical study, not all these students choose for a technical career. Reasons for this are still unknown. As identification with the profession can be seen as one of the main determiners of a successful career, the proposed research focused on the content of the professional identity of technical students (i.e. STEM students) and measured the extent to which STEM students’ personal identity match with the perceived future as an engineer (professional identity). In addition, the identity status, current career choice and the activities to discover the professional field were examined in both qualitative and quantitative way. Structured by five categories, 60 STEM-students from the University of Applied Sciences and the University described their personal identity and the professional identity of engineer. A self-to- prototype matching strategy was used to measure the overlap score between the two described identities. No great overlap was found and in addition, there was only a small marginal significant relation with the level of identification. Remarkably, this relation was negative, what insinuates that students who see more similarities between themselves and their future profession did not identify with it. Besides, the identity status was determined to indicate where the participants were in their professional identity development. Five identity statuses were identified whereby searching moratorium was most popular. A significant relationship was found between the level of identification and the specific identity status a STEM-student has. This does not apply to the relation of the level of identification and the career choice (e.g. function and organization). Lastly, a significant relationship was found between the student level and the career choice. The present study tried to provide insight in the content of the professional identity and what constitutes the career choices of STEM-students.

activities students undertake to discover their professional field. Subsequently, the extent to which STEM-students’ personal identity match with the professional identity of their future profession “engineer”, via self-to-prototype matching (Hannover & Kessels, 2004) will be measured. In addition, the relationship between the overlap of personal identity and professional identity and identification with the future profession will be investigated and subsequently how this relates to the identity status and career choice. Lastly, the current research aims to investigate the relation between the identity status and career choice.

Professional Identity A professional identity consists of personal motives, interests, experiences, and competences that are associated with a professional role (Cech, 2015; Schenk, 1978). According to Van Maanen and Schein (1979, as cited in Ibarra, 1999) professional identity is not only about acquiring new skills, but it also contains adopting associated norms and values of the profession (Pratt et al., 2006). Kroger (2007) adds to this that identity guides the life path of individuals and influences decisions and behaviours. These behaviours, skills, norms and habits are highly different across different professional cultures. For example, whereas communication skills are often valuable for psychologists (Cech, 2014), being practical and good at problem-solving are more typical for the professional identity of engineers (Faulkner, 2000). Professional identity has been studied across different disciplines and has a broad theoretical basis. In the following sections, different theories and models which underlie professional identity will be discussed.

The Comprehensiveness of Professional Identity Identity is a popular concept among researchers in social sciences. The relevance of studying identity is that this concept explains to a large extent the motives behind people’s thinking and doing (Ashforth, Harrison, & Corley, 2008). In other words, identity “helps capture the essence of who people are and, thus, why they do what they do” (Ashforth et al., 2008, p. 334). Different perspectives on how (professional) identity could be studied exist, depending on the type of discipline in social sciences (i.e., educational, organizational, or social psychological). Most theories and approaches are based on one of two widely known approaches: the ego identity theory from Erikson (1950) and the social identity theory from Tajfel and Turner (1979). These two theories will be discussed below.

Erikson, a developmental psychologist. According to Erikson, an individual crosses several phases during the development of his or her identity (Kroger & Marcia, 2011). Passing these several stages determines the personality of an individual and the attitude someone has towards oneself and the world (Munley, 1977). This developmental process that Erikson (1964) described was originally focussed on the development of the child. Later on, the theory was also used to describe the identity in the context of career development of adolescents and adults (Munley, 1977). In career development, the personality develops over time, and is not static. Through the reciprocal relationship between the self and the society, the individual adapts his or her personality (Stryker & Burke, 2000). The ego identity theory helps to define the concept of professional identity in the current study. Central elements of identity formation according to the ego identity theory are commitment and exploration (Kroger & Marcia, 2011). Commitment between the profession and the personal identity could be created by reflection, make use of trial and error, examination of past patterns, and in the end integration to formulate a new, professional, identity (Kroger & Marcia, 2011). To illustrate this, during the final phase of his master a student mechanical engineering evaluates his years of studying, considers his preferences, and is doing an internship. After graduation, the process of exploration continues with searching for suitable and interesting vacancies. By the extensive exploration, the student learns his

preferences and could find a job that meets his preferences. In this way, commitment is formed with the new professional identity. Social identity theory. In 1979, Tajfel and Turner developed the social identity theory (Hogg, Terry, & White, 1995). The social identity theory explains that individuals structure their self-perception by means of the social categories they belong to (Hogg et al., 1995). A social category can be defined as two or more individuals who share a common social identity. These social categories serve as aspects of the self-concept and the related social-cognitive processes form group behaviour (Turner, 1982). In other words, social identification is about locating an individual within a system of social categorizations to define answer the question “Who am I”. The sum of the integrated group memberships into the self- concept forms the answer to this question (i.e., I am an applied mathematics student, a daughter, a member of my volleyball team, I am Dutch), but also describes the way the individual feels or behaves. Comparison of ego identity theory and social identity theory. The description of both theoretical approaches to understand identity emphasizes the complexity of the concept. Some differences between the two theories are important to Note. First, the ego identity theory puts emphasis on the personal identity of the individual, whereas the social identity theory emphasizes group membership. The importance of the personal identity according to the ego identity theory continues in the fact that the personal identity is about integrating the varied aspects of the environment. In fact, there is a reciprocal relationship between the individual and the society. This makes the identity development a dynamic process, in which the identity constantly adapts. This is in contrast to the social identity theory, whereby the identity is only adopted by a social category. In other words, the individual does not develop an identity by his- or herself, but takes an identity and adopts typical characteristics and behaviours that correspond to the group. For example, an STEM-student adopts the identity of an engineer and defines his- or herself only as an engineer instead in terms of several roles. Although there are differences between the two theories, both theories have complementing elements that, together, may form a strong theoretical basis to understand the development of professional identities in the context of work and school. Specifically, both theories emphasize a relationship between the society and the self. In other words, the self is constructed by all the identities an individual has (Hogg et al., 1995; Munley, 1977). Moreover, both theories led to behaviour that is in accordance with the specific identity. Using the ego identity theory, the behaviours stem from the specific role, whereas the social identity theory results in behaviour that is in accordance with the group stereotype. A final similarity is the fact both theories encourage commitment with the specific identity. This last remark is a great value for current research as several studies showed that a high commitment with the future profession is a strong determinant for a successful career (Hannover & Kessels; Pratt et al., 2006; Stryker & Burke, 2000). In recent research, developmental and social psychological perspectives on identity formation are integrated (Amiot, De la Sablonnière, Terry, and Smith, 2007). Amiot et al. (2007) developed a four- stage model of social identity development and integration and combined the principles of the ego identity theory and social identity theory to understand how a multitude of identities can be structured in the self-concept. Current research adheres to this model and also combines both theories. Specifically, this research will focus on investigating the overlap between the personal identity and the professional identity of engineering students. In other words, will the individual adopt the typical characteristics and traits of the professional identity that can be seen as a social group? Based on this theory, the self-to- prototype matching theory of Hannover and Kessels (2004) will be used. The developmental perspective is reflected in the identity status paradigm, which is about exploration and commitment. Both concepts will be discussed later in this theoretical framework.

Elements of Identity Apart from the theoretical perspectives on identity that are described above, identity is composed of several elements. The discipline from which identity is investigated determines the specific formulation. For example, Van Dick, Wagner, Stellmacher, and Christ (2004) investigated the strength of

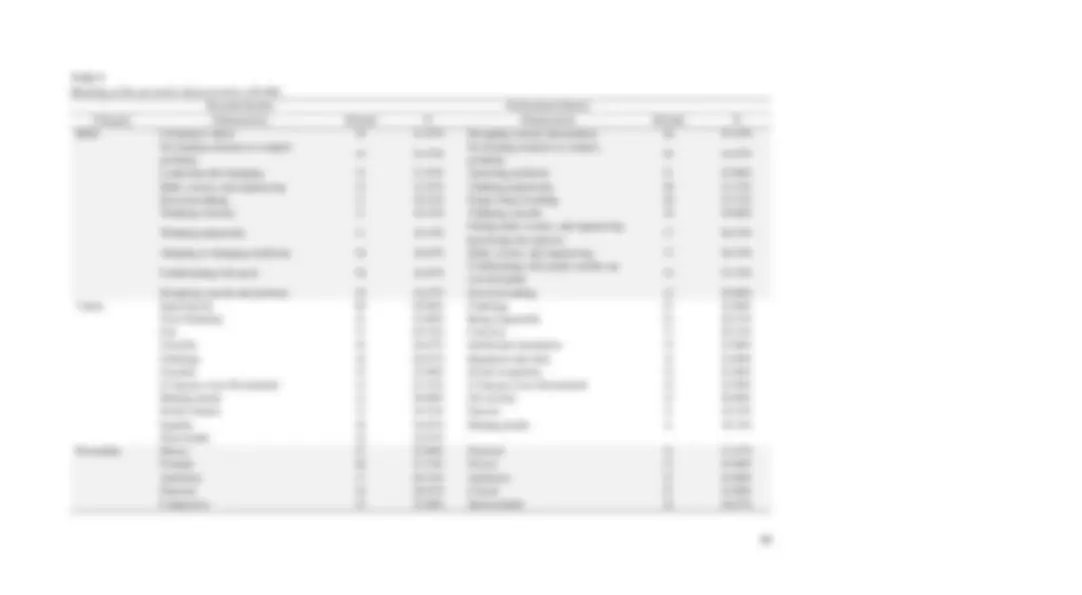

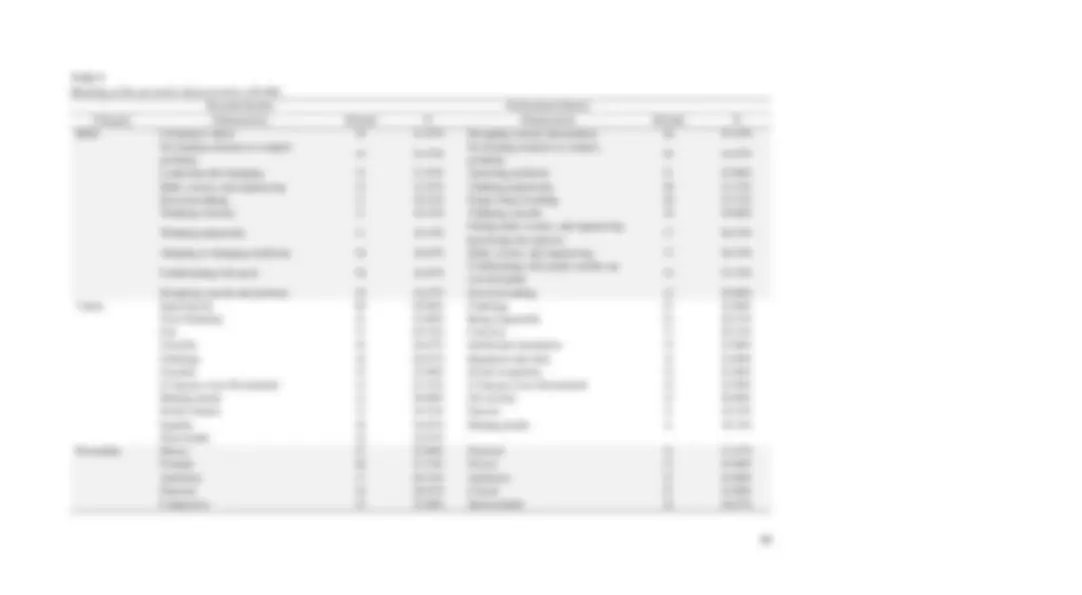

Hannover & Kessels (2004) studied the process of comparing the image of the current self and the image of a group identity, by self-to-prototype matching (STPM). When using STPM, a student lists the characteristics of the self-concept (personal identity) and a prototypical group member (professional identity) and considers the match between these two lists. The higher the congruence between the two, the more likely the student commits or connects to the group. The importance of the self-to-prototype matching strategy is stressed by several studies. Based on knowledge of the self, and characteristics of a future job, students make choices regarding their profession (e.g., Moss & Frieze, 1993; Rounds, Dawis, & Lofquist, 1987; Taconis & Kessels, 2009). A prerequisite for self-to-prototype matching is having a clear self-concept. Hannover & Kessels (2004) concluded in their study that only students with a strong self-concept, can use self-to-prototype matching in order to make choices. Using STPM Hannover and Kessels (2004) asked their participants to rate 65 trait adjectives according how well they described a prototype of a specific subject (1 = not being typical at all, 7 = being very typical). Subsequently, the participants had to describe themselves, using the same 65 trait adjectives and rating scale. The current research also offered adjectives to students, but did not use the same stimuli as Hannover and Kessels (2004). Alternatively, participants had to describe their personal identity and the professional identity of an engineer by means of the five categories of Ashforth et al. (2008): skills, values, personality, goals , and interests (see Figure 1). For each category participants could choose three to five cards with characteristics (based on Möwes, 2016) that could be used to describe the personal identity and professional identity of an engineer. In addition, the current research provided an opportunity to add characteristics by offering empty cards. Core of the identity. Whereas the content of the identity displays the overlap between the personal characteristics of the self and the profession, the core of the identity is focused on the identification with a certain profession. This identification describes the connectedness of the self with the profession (Pratt et al., 2006) and is reflected in the extent of commitment an individual has with the profession (Ashforth et al., 2008). The level of identification can be measured by questions regarding commitment and affirmation. In previous research, Van Dick et al. (2004) showed that social identification plays an important role in the organizational domain. Also related to organizational psychology is research of Pratt et al. (2006) that showed that identification can be seen as one of the main determinants of a successful career (Pratt et al., 2006). From a more educational scientific perspective, Meijers, Kuijpers, and Gundy (2013) concluded that a well-developed professional identity leads to appropriate choices for education and career, fitting the personal identity. As a result, more appropriate choices leads to a lower rate of dropping out (Wijers & Meijers, 1996) and more successful completion of studies. Also from a social psychological perspective identification has been studied, referring to the original social identity theory of Tajfel and Turner (Turner, 1982). According to Mancini et al. (2015) the (professional) identity is a collective identity and related to intergroup processes, and therefore they tried to capture these social processes in identity development. Taken it together, this previous research shows the versatility and the importance of identification. Thus, current research uses the variable identification to get insight in the typical career choices of STEM-students that may offer an answer to the question who leaves the technical field and who does not. Behaviours of identity: the identity status. Current research tries to get insight in the professional identity of STEM-students and their typical career choices. Whereas the content and the core of identity are mainly focused on the internal processes (i.e. self-concept and identification), behaviours of identity is more focused on the associated actions of the individual. The concept identity status, originally introduced by Marcia (1966), bridges the gap between these internal processes (commitment) and behaviours (explorative activities). In other words, identity status is a midway between what Ashforth et al. (2008) would define as the core of identity and behaviours of identity. As described above, the ego identity theory can be used to describe the development of the identity (Munley, 1977). Marcia (1966) elaborated on the ideas of Erikson and used the concepts commitment

and exploration to define the professional development of students. During their late adolescence, students explore the occupational and psychosocial options around them to expand their identity (Marcia, 1966). Exploration can be done for example by actively questioning or weighing various identity alternatives and its values, beliefs, and goals. This exploration could be followed by commitment to the specific identity. By commitment, the individual makes a choice about the implementation of a specific identity. To this end, one could argue that this commitment element of the identity status model (Marcia,

Table 1 Four identity statuses of Marcia (1966) Commitment Low High

Exploration

Low Diffusion status Foreclosure status High Moratorium status Achievement status

In order to capture the dynamic process of identity formation, Crocetti, Schwartz, Fermani, and Meeus (2010) made some adjustments to the identity status model by Marcia (1966.). According to Crocetti et al. (2010), with developing a professional identity, individuals do not start with a blank identity, rather there has been a current identity. In other words, with growing older, individuals have already formed a certain identity. So to form a professional identity, the current identity needs to be adapted instead of developing a complete new identity. Therefore exploration is a two-folded process. On the one hand, individuals monitor their present commitments, named in-depth exploration. On the other hand, individuals explore alternative commitments and decide whether alternative commitments are superior to the current commitments. This process can be named as reconsideration of commitment. Combining the three processes (in-depth exploration, commitment and reconsideration of commitment) resulted in five identity statuses involving a redefinition of the moratorium status. Crocetti et al. (2010) divided the original moratorium status in moratorium status (low score on commitment, medium score on in-depth exploration, and high score on reconsideration of commitment) and searching moratorium status (high score on all three processes). Individuals with the searching moratorium status are seeking to revise the commitments that already have been enacted, whereas individuals with a moratorium status evaluate alternatives in order to find new commitments that are satisfying. The models of Marcia (1966) and Crocetti et al. (2010) emphasize professional identity from a personal, developmental perspective (ego identity theory) as it is mainly focused on the intra-individual processes individuals go through in their career. Based on the motivational and cognitive processes, the personal talents and abilities of individuals will develop. However, according to Mancini, Panari, and Tonarelli (2015) the professional identity not only consists of a personal, but also a collective identity. This means that the processes of categorization, group identification and social comparison are involved as well; processes that are related to the social identity theory. Therefore Mancini et al. (2015) made an

Pierrakos et al. (2009) noted that although these focal points may not be representative for the entire population, their findings were related to students who persisted and switched. Therefore, these findings could offer some information for the pathways students will follow and the career choices they make

Figure 2. Theoretical developments of the conceptualization of identity status

Current Research As identification with a profession is one of the main determinants of a successful career (Pratt et al., 2006), the current research indicates the need for more insight in the content of the professional identity of highly educated STEM-students. Diagnosing different types of STEM-students and their typical career choices may offer an answer to the question who leaves the technical field and who does not. In previous research, Taconis and Kessels (2009) found that the match between the self-image and the image of the perceived future as engineer (i.e. prototype) is a predictor for a science-related career choice The current research follows this reasoning and combines several concepts to gather information about the professional identities of STEM-students. To get insight in the content of the professional identity of engineers, the categories of Ashforth et al. (2008) skills, values, personality, goals, and interests are used to discover the different characteristics. As a match between these characteristics and the characteristics of the self is a main determinant for a successful career, STPM could be used to consider the overlap between the self and the prototype. This is an indication of the extent of identification STEM-students have with their future profession. To support this in a more quantitative way, the items of the identity status paradigm of Mancini et al. (2015) could be used to measure the level of identification and to indicate the status of identity formation. Combining all these concepts leads to a research model that is explained below (Figure 3).

Mancini et al. (2015)

Crocetti et al. (2010)

Marcia (1966)

Identity status paradigm

Identity status

Exploration (^) explorationIn-depth

In-depth exploration

Practices

Commitment

Commitment

Affirmation

Commitment

Reconsidera- tion of commitment

Reconsidera- tion with commitment

To investigate the professional identity of STEM-students, both qualitative and quantitative methods are used. The research consists of a qualitative part and a quantitative part. First the qualitative part is described. In order to guide research, the following research questions are posed:

Figure 3. Research model

Instrumentation Both qualitative and quantitative data was gathered with a questionnaire. The measured concepts are displayed in Table 6. The paper-and-pencil questionnaire was supplemented with a card-sorting activities. In addition to the measured variables of the study, questions about the demographic background of the participants were added. Overlap professional and personal identity. Both the content of the personal identity and the content of the professional identity of engineers was measured by a card sorting activity. The initial idea was to work with a bottom-up approach, from a more grounded theory perspective. This process entailed that participants had to name characteristics to describe them, or the typical engineer, in each of the five categories based on Ashforth et al. (2008). During the pilot-version however, it appeared that this approach did not work well, as it was experienced too difficult by the participants. Therefore, in the final version of the questionnaire stimuli were given. Based on Möwes (2016), each of the categories included 28 to 44 cards with characteristics. For each category they had to choose three to five cards. An example of this activity can be find in Appendix 1. With a bottom-up approach in mind, they could use empty cards to write down specific characteristics that were not included in the presented cards. First, participants chose the cards in order to form their personal identity. Second, they chose cards to describe the professional identity of an engineer. The cards the participants chose, gave an overview of the content of the personal identity and the professional identity of an engineer. To construct the quantitative variable overlap, for each category an overlap score was generated. In addition, an overall overlap score was generated. Level of identification with an engineer. In order to measure the level of identification with an engineer, seven items adopted from the processes commitment and affirmation from the identity status paradigm of Mancini et al. (2015) were used. The reason to use these items for both measuring level of identification and the processes affirmation and commitment was because of the conceptual overlap. Questions about identification and affirmation and commitment had such overlap that participants saw this as duplication. In order to facilitate the questionnaire, it was decided to use the items for measuring two variables. An example of an item from the variable level of identification was: ‘Thinking of myself as an engineer makes me feel self-confident’. Participants filled in to what extent the propositions suited them by means of a five-point Likert scale (1 = totally disagree, 5 = totally agree). A sum score indicated the level of identification with an engineer. The reliability of this scale was high, α =.84.

Table 3 Example questions of the five categories adapted from Mancini et al. (2015) Category Question Affirmation I am looking forward to become an engineer In-depth exploration Do you ever think about the advantages and disadvantages associated with becoming an engineer? Practices Do you ever participate in meetings/conferences where professional engineers speak? Commitment Thinking of myself as an engineer makes me feel self-confident Reconsideration of commitment If I could change my choice of becoming an engineer, I would do that

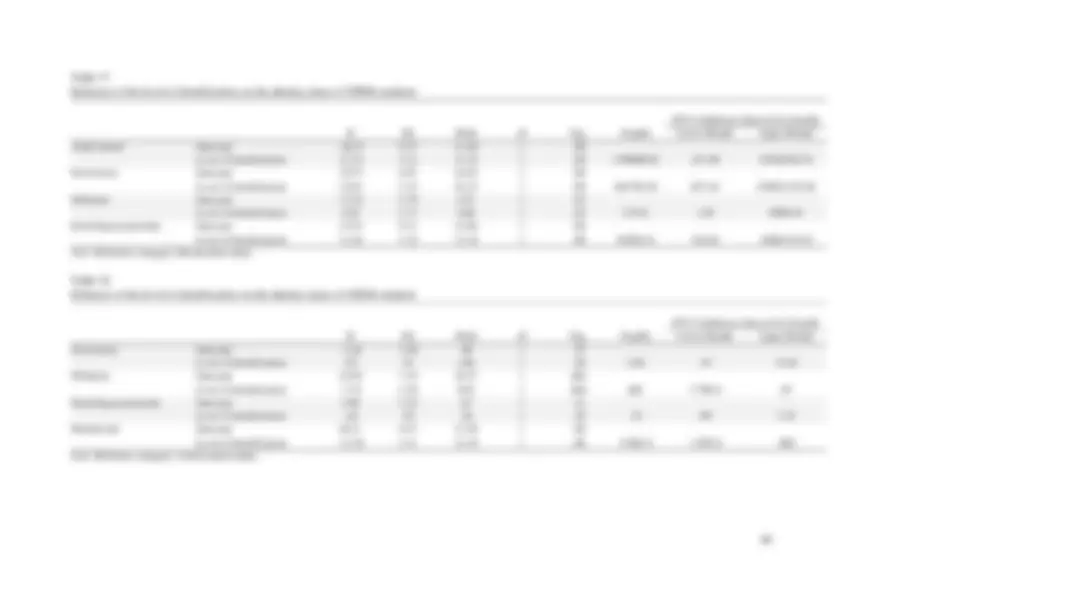

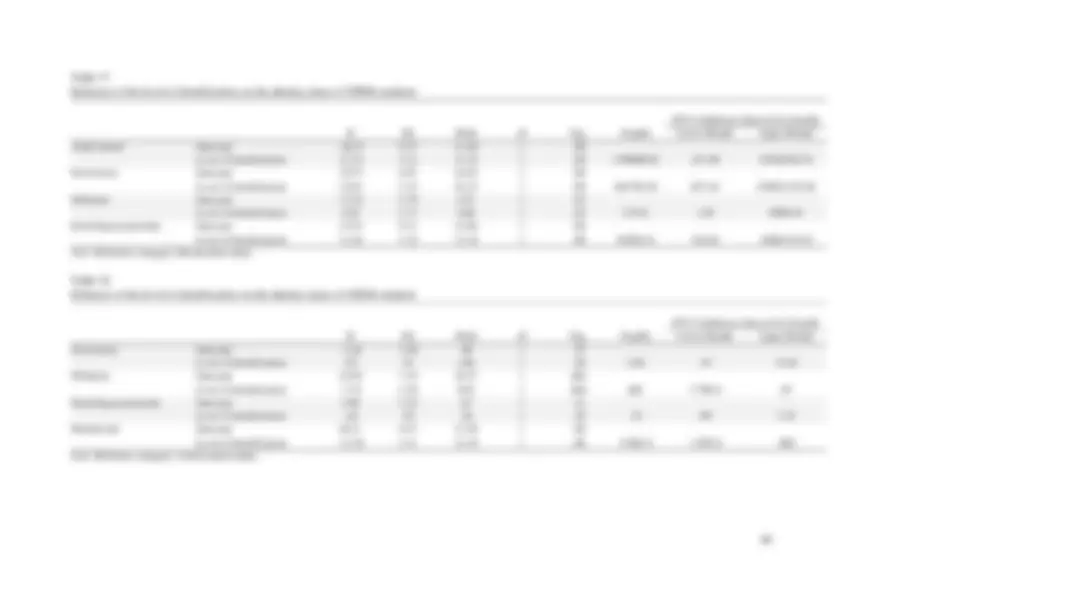

Table 4 Summary of exploratory factor analysis results for the SPSS identity status questionnaire (N=60)

Rotated factor loadings Item Level of identification

Reconsi- deration of commitment

Practices In-depth exploration

Thinking of myself as an engineer makes me feel secure in my life. Thinking of myself as an engineer makes me feel self-confident. Thinking of myself as an engineer helps me to understand who I am. It is important for me to become an engineer. I am proud to become an engineer. I am looking forward to become an engineer. I am feeling good at this moment in time as future engineer. If I could change my choice of becoming an engineer, I would to that. I think that it would be better to prepare myself for another profession. I am considering the possibilities of changing my study program in order to be able to practice another profession

.

I think choosing a different profession would make my life more interesting. Do you ever read books/articles written by engineers?. Do you ever participate in meetings/conferences where professional engineers speak?

.

Do you ever seek information about the regulations of the engineering practice?. Do you ever think about the advantages and disadvantages associated with becoming an engineer?

.

Do you pay attention to what other people say about engineers?. Eigenvalues 3.50 2.40 2.22 1. % of variance 21.89% 15.00% 13.86% 10.76% α .84 .70. r .36* Note. * = p <.

Identity status. During the pilot version, questions from Crocetti et al. (2010) were used to measure the identity status of the participants. During the process of piloting, a new version of the identity status model by Marcia (1988) and by Crocetti et al. (2010) was published. Therefore, it was decided to use the questionnaire by Mancini et al. (2015), adapted to the current research purposes. Participants answered 19 questions that were divided in five categories: commitment (four questions), affirmation (four questions), practices^2 (three questions), in-depth exploration (four questions), and

(^2) In the questionnaire by Mancini et al. (2015), the subscale ‘practices’ consisted of four questions. However, since the current survey already contained an open question about the activities students undertake to discover the professional field, the question ‘I seek information about the different job options that a degree in engineering may offer’ was deleted.

were quantified by one researcher by dividing the answers in technical and non-technical profession and organization. For example, ‘designer’ was labelled as a technical function, whereas ‘project leader’ was labelled as non-technical function as the job is mainly focussed on managing and controlling and less on designing. Career exploration activities. To list the activities students undertake to discover the professional field an open question was asked: ‘What activities do you undertake to discover what kind of work you want to do after graduating’. All answers were entered in Atlas.ti, coded and categorized. Demographic background. In order get insight in the student background information, additional questions about the student and its study were added. Concepts are displayed in Table 5.

Procedure Before the data collection, that took place form December 2015 till the end of January 2016 could start, participants of the University of Twente and Saxion had to be selected. Participants of the University of Twente were recruited personally and the snowball method was used to approach more students from the University of Twente. Besides, participants of Saxion were recruited via a contact person and personal contact during project hours. The participation was voluntary and all participants made a personal appointment with the researcher to fill in the questionnaire. Most participants had an individual appointment, some participants had an appointment in duos, but also filled in de questionnaire individually. During an appointment participants filled in the questionnaire. The questionnaire started with a spoken and written informed consent about the purpose of the study, the process, risks and benefits and the use of the results. After a written confirmation of participation, the participants started with part 1 and described their personal identity according to the five categories of Asforth et al. (2008) with a card- sorting activity. This was followed by part 2 that consisted over the demographic characteristics of the participant and part 3 with questions about the participant’s study. In part 4 participants performed again a card-sorting activity based on the five categories of Asforth et al. (2008) again, but this time they described the professional identity of an engineer. Part 5 was formed by questions about the affirmation participants had with their future profession. The questionnaire was completed by part 6 with some final questions about the research. Completing the questionnaire took about 30 minutes per person. All participants were personally supported by the researcher in case they had questions. As a thanks, participants received a gift voucher of five euros. The research was performed according to the ethical guidelines of the University of Twente. Before the data collection started, an ethical form was filled in and approved by the ethical committee of the University of Twente. As mentioned above, an informed consent took place before the participants started with filling in the questionnaire. A debriefing session was not needed as the participants were fully informed prior to the study, and the risk of stress or discomfort was minimal. The anticipated benefits of participating were higher than the risk. In addition, there was no question of a relation of dependency between the researcher and the participants. However, in contrast to a positivism perspective, the researcher was involved with the participants as it was a one-to-one situation. The researcher did not had a distanced role, but created a workable atmosphere for the participants in order to complete the questionnaire (Mertens, 2014). The data was handled confidentially, as the names of the participants were not used in any published or written material concerning the research. Only the researcher and the supervisors had access to the interview materials (Babbie, 2010). Participants could fill in the e-mail address to receive their personal and general results of the research.

Table 6 Measured components of the research Component of the study

Measured concepts Measured by Example question Measurement level

Overlap personal identity and professional identity

The content of the personal identities and the future professions consisting of the 5 categories of Asforth et al. (2008)

3 to 5 answers per category compared with the Self-to- prototype-matching strategy of Hannover and Kessels (2004)

String (Open questions)

Level of identification with an engineer

Identification score 7 questions of the categories commitment and affirmation of Mancini et al. (2015)

“Becoming an engineer is important for me”

Interval (Likert scale: 1 = totally disagree, 5 = totally agree) Identity status

Individual identity status of the participants:

A final score compromised by the scores of the 4 categories:

“I think another profession would make my life more interesting”

Nominal (Likert scale: 1 = totally disagree, 5 = totally agree)

Career choice

2 open questions about the future profession “Please give an example of an organization you would like to work in the future”

String (open question)

Career exploration activities

“What activities do you undertake to discover what kind of work you want to do after graduating?”

String (open question)